Thanh Tâm Tuyền: Quicksand

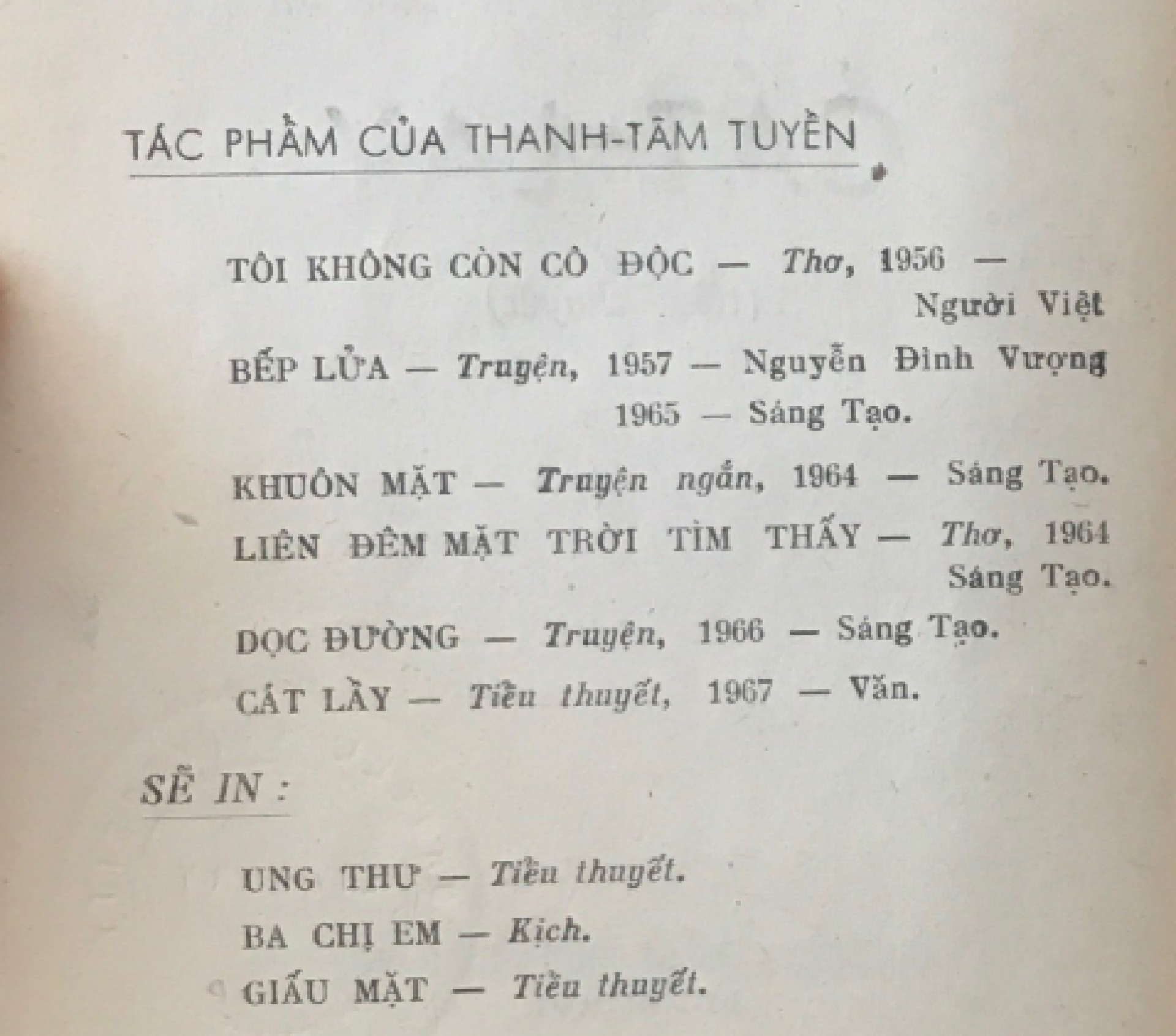

Tiếp tục kỳ thứ ba của chương trình đã bắt đầu vào cuối Hạ (kỳ thứ nhất & kỳ thứ hai), song song với marathon lý thuyết ở kia. Lần này là một tiểu thuyết của Thanh Tâm Tuyền, Cát lầy, viết trong ba năm, từ 1963 đến 1966. Bản dịch dưới đây là toàn bộ phần đầu (trong tổng thể bốn phần), theo ấn bản Giao Điểm, in xong ngày 20 tháng 7 năm 1967.

Quicksand

- Thanh Tâm Tuyền

The loneliness of the small town’s afternoon hovered around the street corner. The sunlight, like a stagnant flame—bright but not blinding (a flame of impotent desire)—veiled the façades of tightly shuttered houses. These had once been bedrooms, each with brick fences stretching toward the road, greedily claiming a patch of cement pavement. A side wall of the one-story house at the far end of the main street cut sharply into the corner, weathered and stained by seasons of rain, streaked with moss, framed by layers of shabby, overlapping advertisements and propaganda. A worn paper arch, erected once for all manner of festivities—now a dull brown with traces of faded gold like the ghost of joys long grown stale—turned its back on the bright patch of sunlight in front of the town's administrative office, its gaze resting on the flowerbeds lining the main street, winding toward the market, the bus station, the riverbank. Things emerged abruptly, twisted into isolated forms, like a scowling face. The present felt distant like a faint laugh. The oppressive pull of material things and the forceful push of the void clashed, and the mind crumbled—passive, drained—like old plaster suddenly falling into ruin.

The sky gradually softened, descending in folds like a thin shawl adrift in the breeze. The scene gathered itself, rose, and enclosed. The afternoon, hazily drifting from days past, settled into a fleeting instant of murky ambiguity. From the distant hills, children's laughter echoed through a dense canopy of trees. A car horn, stifled and strangled, let out an unrelenting wail. A sharp, metallic cry melted into thin air.

The dirt road, sloping and hard with pepples, merged into the main road leading to the market and the highway skirting the town, leading up to the plateau. The row of houses had about ten in all, with the last one precariously perched at the eroded edge of the highway—its smooth, green-stoned corners gazing across a dense banana grove, separated by a sluggish, muddy stream. This was where Hiệp and Thuận had once lived. The two wooden doors were tightly locked and barred, every crack sealed like eyelids pressed shut. Thuận had died. No one lived there anymore, and perhaps no one ever would. The doors would remain shut forever.

During the war, a family had taken their lives inside that house. They had temporarily fled to the province from Saigon. The husband arranged a safe place for his wife and children, while he himself ventured deeper into the resistance zone. One night, returning home, he caught his wife right in the act of betrayal and stabbed her six times, strangling the four children before taking his own life. The house lay abandoned for some time. The head of the provincial Public Security Office eventually bought it at a low price. Whether out of some peculiar sympathy or for reasons tied to his own interest—no one knew, he later assigned a man from the North, who had been relegated to this province due to “political behavior,” to live there. The Chief arranged for a subordinate to both handle the household tasks and discreetly monitor the man. Nobody ever saw his face; he never emerged from behind the closed door of his room; even the neighbors heard no sound.

Occasionally, the Chief of Public Security, after work or in the evenings when free, would visit the detained man for conversation; people only ever heard the Chief’s resounding voice, but never any response, as though he were speaking to some ghost. One morning (the dawn as raw as a fresh wound), the staff responsible for surveillance discovered that the man had committed suicide, along with the woman who had visited him the previous night, brought in by the Chief himself. The man had been held for a whole year without incident, so the staff, feeling secure in his duties, had gone out to watch cải lương the previous night and returned home to sleep with his girl, leaving the man and the woman alone. The two had used a razor blade to sever their wrist arteries, and by the time the staff returned, they had long since died. The young, beautiful woman had been dressed in white—some nearby witnesses had briefly glimpsed her stepping down from the Chief’s jeep—perhaps the detainee’s lover who had traveled all the way from Hanoi to see him. Because of this incident, the Chief of Public Security was transferred out of the province and sold the house cheaply to Diệp’s mother. The house remained locked and vacant until Hiệp and Thuận rented it after the migration.

Chị Thuận. Chị Thuận. It’s me Trí. Beyond that door is the realm of death, and I cannot step inside. I stood outside, pressed against the wall, drenched like a rat, in the stormy downpour of an October night. I slammed into the door, beating at every panel, crying out in desperation: Chị Thuận, chị Thuận. It was three or four in the morning, the rain drowned out my screams. In that moment, I knew nothing yet; I only sank deeper into fear, a fear that built and surged into panic, fed by oppressive imagination. I never suspected Thuận would embrace death so tightly, entwined with so many accomplices. Chị Thuận, chị Thuận. The door doesn’t open, will never open again, closing off what I wish to see. No one is behind it now. Hiệp, Thuận, and Diệp.

From afar, I gazed at the sloping brown-tiled roof, calm as a sweeping wave of hand. During the time Hiệp and Thuận lived there, the outer door rarely opened. Once each morning, a passerby might catch sight of Hiệp sitting, drinking tea, smoking, waiting for the hour to leave for school at the table in the middle of the living room; in the cooler afternoons, Thuận would crack the door to let in more light for her work, sitting by her sewing machine near the door to the inner room, her slim side profile quiet and intent. Each time visiting from Saigon, I would hesitate at the doorstep, reluctant to disrupt the emptiness. Whether Hiệp and Thuận were present or absent, the house bore no trace of it. Peering through the window, I could see bare plastered walls, free of any art save for a bright red calendar hanging near the sewing table (a slender golden reed against a blank, shiny background, solitary). The furnishings were sparse and orderly: simple wooden tables and chairs, the sewing machine with its small stool, a green canvas recliner propped against the wall. The house still seemed to belong to nobody, and each time I felt as though I were standing just beyond the intimate circle of everything within it. I would sit on the smooth, polished chairs, with seats and backs that sloped in a clear, deliberate curve, armrests firm and sharply shaped, looking across the grain of the round table, the green walls, their faces, their movements and gestures—looking and finding nothing but illusions. Hiệp and Thuận drifted beside each other in a stillness so deep it seemed they, too, were objects left untouched, orderly, pristine. Outside, the road rarely saw traffic; now and then, a horse-drawn carriage would rattle up or down the short incline in front of the house.

Thuận died in the inner room, where I had never set foot. A curtain of flowered fabric, bunches of pale yellow chrysanthemums, hung soft and heavy over the doorway. I often pictured it and imagined, surely rightfully, that it was the secluded place belonging only to Hiệp and Thuận. The wide bed with a flat mattress seemed untouched, the large, heavy desk immovable, and the wardrobe lacked a mirror (why no mirror?). Empty spaces were left so two people could move without bumping into each other. A window opened to the yard, revealing a patch of sky framed by tree branches thick like a forest, the tops of trees from the hills behind the house. The narrow yard was clean, with no water tank, only a black tar-coated drum, chest-height (Thuận had to stand on tiptoe to check the water level, her hair tilted to one side in the lighted nights of summer) beside several thin metal barrels lined up neatly. One rainy afternoon, I sat alone in the living room with the large barrels placed outside, while Hiệp and Thuận went to collect water. The downpour roared onto the thin drum. During the dry season, Hiệp and Thuận would load the barrels onto a metal-wheeled cart, pushing it to Mr. Pháp's house to fetch water.

The boat turned sideways, leaving the market dock. Early in the fruit season, boats crowded the shore, piled high with mangosteens, durians, rambutans, jackfruits... The broad seven-plank boat, with only two passengers crossing the river—a young man leading a new motorbike with a large headlamp jutting forward from the handlebars—aimed its bow toward the floating café. The café, framed by wooden rails forming open rectangles crossed with lattice, sat open on all four sides. Tables covered in red and green nylon cloths were still empty; the four sloping roofs met at the peak. The afternoon grew soft, nearing the point of swift fading. From the fort on the elevated ground, where the river fanned out, came the fading echo of brass horns, a patch of dull gold sound like fading sunlight. The tree-lined road stretched along the riverbank, straight and flat as it left the town, crossing a short bridge over a shallow canal, the asphalt turning into red, dusty earth, lying at the foot of the dense hills where the province's government buildings nestled. Behind the dense clusters of nipa palms along the river, a late bus bobbed along, moving slowly on the road linking the districts.

The large river was gentle now. Gone was the wild bite of the water under the scorching midday sun as one waited for the boat, its surface glaring like an immense mirror, its edge broken by evasive, unruly clusters of grass, stretching endlessly like the ví dầu, hò ơ lullabies my mother used to sing to the illegitimate grandchild born in the kitchen. Gone, too, was the terror of stormy nights, lying alone in the attic beside the window, naked under a blanket, the sleep restless, wandering somewhere beyond reach, hearing the howling wind blowing upstream, echoing through the empty fields, rattling the palm leaves, the garden trees, and the water rushing endlessly in the distance, as if the river might swell into something monstrous, devouring the houses and fields whole. The feeling of total dissolution into the brutal force of nature surged through the body burnt to paralysis with desire. By morning, the house was free of its old mildew, the earth softened, leaves wet and limp, water gushing all around, filling the canals. The body felt strange, like the misty sky hanging low over the fields. I lowered my hands into the water; it rose to my wrists, surging upward, parting at my touch. Youth slipped away like the slick current slipping through my fingers, leaving behind only a warm sensation and the weight of something lost. Youth stayed veiled behind Thuận’s death, behind Diệp’s death, leaving only the foggy numbness of my mind, an absolute silence from which my body emerged, still holding onto the twilight stillness.

Darkness smeared the shore ahead, sinking it lower, level with the water. I was still in the middle of the river. The oars slapped the water, heavy and rhythmic. The young man rang his motorbike’s bell a few times, the playful sound drifting across the water. Beyond the shrinking treetops, the town lights flickered on in bursts, pushing back the darkened streets at the base of the hills. The market glowed faintly, its stalls lit by gas lamps. Lights hovered mid-tree height, facing the town; they would grow steadily brighter before fading, drifting with the night. One of those nights, I had burst through the door, running wild in the rain, driven by a shapeless urge. On the muddy paths along the waterlogged canal, where the air reeked with swampy rot, each drop lashed my face like a whip, until I was nothing but the flailing of limbs and gasping breaths. I leapt into the water and waded. Not this river, with its quiet, slanting surface, but the other river, with its cold, fierce embrace, tightening around my face with the brutal force of childhood memory. Swimming out a few dozen yards, I turned and floated, gulping down patches of rain pounding onto my face. You are Trí, you are Trí. You’re not mad. No, I’m unable to be mad. Dragging myself up onto the shore, hearing my mother and Lệ crying to me through the rain, thick as a tight net, across distant gardens beneath a dim sky that seemed to lighten toward dawn. Running back, I crouched in the dog hole outside the fence. Let me in, somebody. It’s freezing. Where are you, Trí? What’s wrong, Trí? What’s happening, Trí? I went to the river to bathe. Don’t worry, Mother, I’m not mad. Let me sleep. Bathing in the river at this hour? Good heavens. Take some ointment, child. Just toss it here for me. I’m naked here. I wrapped myself in a blanket, curling up, my limbs weary and limp. The biting scent of the ointment made my eyes water, that hollowness tightening around me, enclosing me. The rain grew fiercer. The river surged and roiled out there, streaming into the sleep. You are Trí, you are still Trí.

The boat drifted slowly, veering with the current. The boatman leaned back against the pale gray expanse of sky, gliding to the rhythm of his oar. The young man stood mid-deck, now and then pressing the bell, listening to its faint chime. I sat at the bow, holding a dented tin can, scooping water from the bottom and pouring it back into the river.

The young man hoisted the motorcycle onto his shoulder, stepping over sunken stones in the mud to reach the shore. He set the bike down, leapt onto the seat, the vehicle swaying unsteadily as his feet dangled, searching for the pedals. Finding his balance, he pedaled quickly along the narrow path between clusters of bushes. The bell rang frantically, the battery whirred with the turning wheels, the chain clicked over the sprocket teeth, and the sound faded around the bend.

The chickens had settled in their coop, leaving only the faint clucking deep in their throats and the rustle of straw. At the sight of someone passing by, the dogs retreated behind the fence and barked wildly. The dim oil lamps flickered like murmurs within the houses. Thin, faded darkness from the empty fields and river spilled into the garden, thickened with the pungent, blended scents of meadow grass, muddy earth, and canals. Somewhere, a radio voice droned, the announcer’s tone steady, neutral, creating an oddly haunting rhythm. In the dense cluster of nipa palms, a few strange streaks of light slipped through, as if it were still daytime on the other side of the creek (a day in another world). This road no longer led me home; I was passing by once again in life. For the last time, wasn’t it?

I pushed open the gate and walked along the narrow path of single-file square bricks, crossing the front yard—filled with the scent of night-blooming jasmine, shadows of potted plants, a sparse Jamaican cherry tree, a guava with thin branches, a plum tree, a dense-leafed cashew. I stepped up onto the porch. The tiled roof sloped low behind me. I paused at the threshold, the wooden bar striking against my shin. From the realm of the dead, I had come home. A dim light flickered down in the side house while silence blanketed the main house. I knocked softly on the door. The beam of light on the porch wavered, shifted. A raised lamp appeared in the doorway, casting light forward and pushing my mother’s face back into shadow.

— Who’s there?

Her voice wavered like the light. I managed to utter: “It’s me, Trí, mother.” The door opened with a dry creak, stretching into silence. I squinted as the lamp rose to eye level.

— Oh, it’s you. Trí.

She stepped aside to let me in, stammering, “Trí, where have you come from?” I entered, walking into the open space within the four central pillars of the house and stood there, silent, neither saying or thinking anything. My mother set the lamp down on the wooden bed near the door and sat beside it, weeping. When my father died long ago, I’d told her, “Don’t cry, mother,” and she’d stopped immediately. The bed, a bit uneven, was propped up on broken bricks. That used to be where my mother and Lệ rested. In the corner diagonal from the wooden bed was my personal area. A narrow iron bed for one person, with a tall, awkward mosquito net post. On the desk, books and notebooks were stacked more neatly than before. Outside the window was the star-apple tree with thick leaves. Those things belonged to me, unmoved in the slightest during my absence. Even if I had died or were to die tomorrow, my presence would still remain. I had marked it among my relatives, by imposing, by stubbornness, by selfish cruelty. Those things stood firm in an unruly way, like my own unruly existence. Next to the wooden bed, on the solid black-lacquered wooden cabinet of clothes and everyday things, was a small altar for my father. My kingdom stretched from the window to the front door, with no by furniture except for two empty benches shoved against the wall, unused. No one had passed through this front door in recent years, except for me. Visitors coming to see my mother or sister Lệ would circle around the back, entering through the side garden. I lived in defiant isolation, completely sealed off in my own world.

“Where’s sister?” I asked.

“She went down to Đình village.”

I moved to sit on my bed. My mother wiped her tears with her sleeve, bolted the door, and went downstairs. The lamp stayed on the wooden bed, its flame flickering up now and then, dancing in spurts. A little later, she returned, opened the cabinet, and rummaged around for a mosquito net and blankets, which she folded at the foot of my bed.

“Have you eaten?”

She looked up at me, stepping back slightly, waiting for my reaction: a flare of sudden anger, sharp words, curt replies. But I only furrowed my brow and smiled. She was surprised, holding onto the bedframe, her shadow faintly outlining the edge of my field of vision, no longer weighing as heavily on me as it once did.

— Are you staying home for good?

No. I returned from the death not to stay. Not to stay. My body had become hollow, desolate, emptied out of all impulse or longing, shrouded in an endless wind of a black void. Perhaps my mother was also aware of that. She had long known that she had lost me. She fell silent, sighed and smiled faintly.

— Why haven't you come home? Why didn’t you let us know? When we got the news, I and your second sister came looking for you, but you had already gone…

I couldn’t answer. The truth is I no longer remember the days that passed, what I did, or where I went.

Death’s near miss bleached a stretch of days; I had nothing left but this “I” — a trembling void. You are unable to go mad, if you can, how happy you would be. I fixed my gaze on Thuận’s portrait, untouched, still encased within its frame on the top of a stack of books. Her eyes, distant and searching, stared ahead, past me as if trying to grasp something lost in the shadows behind. Her smooth black hair framed her face with solemn grace. I encountered this portrait in one of the books borrowed from Hiệp and stealthily took it away, its faded ink looked as if it were a charcoal sketch.

— Poor Diệp. Her parents have gone down to the six-province region.

I kept staring at the woman in the portrait. After a while, my exhausted eyes grew blurry; when I startled and looked back, I saw my mother already turning her back, heading downstairs. I was left with my solitude: sorrowful thoughts settled on my face, only to swiftly vanish like bird shadows darting across the dusky afternoon sky.”

Just moments before, the sky had been a clear blue, with dark clouds drifting through the garden, resembling flickering sulfur flames. The full moon was rising. The blushing horizon slowly shaped itself into an umbrella floating upward, a glowing orange bubble refusing to be sucked into the earth below. It rose and rose, then froze, hanging still. Across the field, the stream gleamed glaring white, and the water beneath flowed more swiftly, desperately.

The house had sunk into the shadow of the surrounding trees, like a tomb. The four damp walls, covered in moss all year round, the roof old and worn like an ancient temple, the red bricks polished raw from daily scrubbing. The stagnant air inside, like a trapping web of love woven by two widows, tightened its grip around me, its sweet prey. (The prey thrashed wildly in resistance.) I stood outside. The moonlight blazed with a terrifying brightness unlike anything I had ever witnessed. The tender vibrations of everything enveloped me in. Happiness gently caressed the senses. Happiness unexpectedly revealed a treacherous doorway, a distant and empty blue. Happiness desperate and teetering like a singing voice rising, chasing time. Unreasonable happiness that shouldn’t exist, ignited from the hidden destructive force deep within me, happiness that I had once fiercely resisted. Perhaps it was destiny tightening its grip from that moment on.

“You’re so strange. You’re afraid of happiness.” “Yes, I am afraid of happiness.” “No, you’re not—if you love me.” “I love you. I love you. But I’m afraid.” “No, you don’t love me. You want to die before I do.” “Diệp, Diệp,” I suddenly whispered her name.

I stood by the water, hypnotized by the illusion of light and form surrounding me, powerless to resist. The force that had once stirred within me was now extinguished. The wind carried fleeting leaves over from distant fields, rustling across the swelling water. I listened to my breath in silence, erasing myself to a senseless state, like a tree in the garden. (The vague footsteps of all creation brushed through my body.)

Suddenly, I heard my mother’s quiet sobbing inside the house, clear and close, jolting me from my stupor. I stayed motionless, paralyzed until I startled again—when did her sobbing stop?

A cry melted into the flowing stream of light. I turned around. Lệ was standing under the shadow of the star apple tree, holding her child. The little one’s head drooped onto her shoulder, her shirt gleaming white. Her face was an oval glow, half-hidden beneath the shade of the tree.

— Trí, is that you?

She shifted the sleeping child to the other arm. Stirred, the baby letting out a faint moan, and she hummed a lullaby, though no clear words formed. She waited for the baby to fall back asleep before going quiet herself. She stood still, facing me, her free arm raised hesitantly, awkwardly. Perhaps she was brushing her hair, though all I saw was a long white shape vibrating.

— When did you return?

She stepped forward, a few hesitant steps, stopping in a patch of moonlight. The distance between us was measured by the vibrating silence. In the moonlight, she became fully visible—full and calm, her eyes drawing in soft reflections of wet, green light. Her hair had been cut short to the nape, shaggy and rough, and she held her headscarf in her hand. I knew she had shaved her head to pray for her brother’s safety, just as she had when I was sick years ago. Her hair, soft and wet, had once been the most beautiful in the village when she was a girl. Now, with her cropped hair, she looked like a young spirit medium, haunting and strangely sensual.

“Go inside and let little Liễu sleep,” I said.

She turned slowly, hoping I might say more, her shy steps echoing in her shadow. Her small silhouette was swallowed by the darkness of the house. She didn’t light the lamp, but groped her way through the night. I didn’t pay much attention but could still hear the faint, unmistakable sounds of movement. My mother was still awake. Lệ was singing softly as she laid her child down in the crib, and my mother cleared her throat. The quiet swelled, filling the space with the rustle of grass and insects. I could hear water splashing as someone washed their feet by the porch and the sound of wooden clogs clicking on the stone floor. I gazed into myself, as if I were someone else standing in the midst of an endlessly green-blue night, endless like a block of shimmering crystal.

The morning air bloomed redolent in the garden, with a vague purple haze hovering at the edge of sight. The shadows of leaves shifted in the window frame, like the arc of a deep forest path illuminated by soft light. Sounds echoed through the village, the crisp roar of a motorbike rolling towards the dock. My mother and Lệ were chatting somewhere down in the kitchen. I lay there, paralyzed and restless, a numb weariness settling in, trying to anticipate each gesture I’d have to make once I got up.

Little Liễu fumbled her way beneath the bed, hands reaching to grab the mosquito net. She clung to the iron frame, walking slowly, her eyes peering through the thin fabric of the netting. Her long, wet, clear eyes sparkled, and she broke into a gentle smile, just like her mother. I lifted the net and crawled out, my legs dangling, calling to the little one. I reached out, wanting to pull her closer, but she shrank back, her eyes still locked on mine, her mouth quivered, the tremble growing more and more pronounced. Stumbling, the child let go of the iron bedpost and collapsed onto the tile floor, bursting into tears.

— Here comes mother. Look, just your Uncle Three here. Your Uncle Three.” Lệ scooped the child up, patting her gently on the back, repeating over and over:

— Your Uncle Three is home, your Uncle Three.

I forced a smile, then went downstairs to wash my face. Lê was still soothing her: “Come now… come now… let mother fold the net for Uncle Three.” My mother hunched over the canal, fetching water to tend to the lemongrass and mint bushes in the corner of the garden. I looked up at the areca palm, avoiding eye contact with anyone. My journey had taken me too far away, estranging me from everyone. I couldn’t bring myself to tell my mother that this would be my final visit, that after this I would disappear. I would vanish forever, carrying with me the empty spaces I had carved out in this house.

All these years, I had already vanished. I belonged somewhere else. To me, family was a prison, strangling all hope with gentle, caressing hands. My relatives, showering me with their muddy love, only blurred the distant horizons of my youthful dreams. I resisted by evading and hiding all feelings. The horror of drowning in a stagnant pond of happiness, of suffocating my unique existence. I dreamed and dreamed, developing habits of spiteful rebellion and insolent resentment, building walls to separate myself from everyone around me. The thick walls of self-consciousness tightly locked me to suffocation, turning me irrational and violent. Short bursts of conscious madness followed by relentless guilt and regret—an unending cycle, hollowing me out. To my mother and Lệ, I had become a stranger, living in the house like a domineering, selfish guest. I drove them into mere shadows—cumbersome shadows. My loved ones had to be banished from my world, for my fierce existence demanded the destruction of all other existences. I sucked in all freedom for myself. They timidly wandered down in the annex, or in the garden, among the sympathetic animals. I took over the upper room, sharing it only with a dead man—my father. All I could ever see was myself, all I could ever hear were the endless chaotic voices swirling in the void hidden within me.

My father died from madness. I kept repeating to myself: You’re not mad. You will never go mad. He used to drink wine in the dusk, during meals. When my mother and siblings left the tray, each going their separate ways, he would sit there, dazed, on the wooden plank. The alcohol began to seep in, his face turned ashen, his eyes bulged as if they were about to pop out of their sockets, gazing fixedly at a point, as though it were a crack into another world. He sat still, said nothing, never screamed, then he would climb into his hammock and fall asleep, in the twilight of the evening. One day, tears streamed down his motionless eyes, like snails floating dead in a bowl of fish sauce.

I cried out: “Look, sister. Father is crying.”

Lệ pulled me by the hand out to the garden, where we stood beneath the jackfruit tree. The dying sunlight stretched over the newly erected watchtower, the riverside weeds were freshly cleared, the barbed wire twisted and coiled like giant pythons. Sometimes he would climb into the hammock, unconscious, foams spilling from his mouth. The women would rush around frantically, trying to save him. I slept beside him, my body bathed in the hot fumes of his breath, mixed with the stench of alcohol and medicated oils; his breathing was thick, wheezing, clogged. One night, he began to sob, a pitiful cry. His sobs convulsed him, shaking his body violently as if he were seizing, the terror spreading through the thick, cold wooden planks. My mother had to summon the shaman to drive away the spirits. Candles were lit in the middle of the night, the neighbors gathered, and the dark fields outside felt as if they were closing in. The drumbeats clanged along with the shaman’s incantations, mingling with his savage howls as he performed the exorcism, dressed in a bizarre outfit: a scarf wrapped around his head, a red sash around his waist, two flags crossed behind his back.

The haunted patient sat cross-legged on the wooden platform inside the house, staring out the window, himself also muttering incessantly. Suddenly, he appeared at the threshold, behind the altar, laughing hysterically. The sound thick and murky, shattered like broken pottery. The shaman pointed at him, made hand signs, and shouted. My father lunged forward, arms flailing, and everyone scattered in panic, running for their lives as if a Western army had stormed the village. My father grabbed a knife and chased the shaman, wildly slashing at the bushes before collapsing into the canal. From then on, night after night, his cries and laughters grew longer, stretching on until he ran out of breath. During the day, under the midday sun, he would climb onto the roof, tearing his clothes apart, his wild beard sprouting in every direction, sitting cross-legged and chanting Buddhist prayers. In the end, during the curfew, he broke the door down, ran to the river, and waded towards the French garrison. The soldiers on the watchtower fired. His head bobbed in the water, illuminated by the harsh spotlight, sluggish and dim. My mother and sister, hiding in the bushes by the shore, screamed out, “Father! Father!” His body washed up two or three days later, drifting into the canal behind the house as the water receded.

In those suffocating days, I often wanted to go mad like him, to bury the world in oblivion, to drown myself in a swirling abyss of darkness. But I couldn’t. I could never go mad, not in this lifetime. You’re insane, truly insane, Diệp said. You want to go mad. Mad like a storm raging over a desolate plain. The bleaching out of days and nights was like a violent self-activation of a consciousness trying to hide, to negate itself. I was incurably sober, and I was numb. I returned to the old place, but not as a wayward son seeking forgiveness. No, I returned to confront my Fate, for I must live out my Fate.

When I finally held Liễu in my arms, gazing into her dark, glistening eyes, her sweet breath softly puffing against my cheek, I didn’t know what else to do. Her tiny hands grasped at my pale earlobes, and I burst into a snorting laugh: it tickled too much, you brat. Lệ stood in the corner, staring at me intently, half-pleased by the rare sight of my amusement, half-anxious, as if I were some sort of beast that might harm the child. The adult’s dumbfounded gaze, paired with my loud exclamation, startled Liễu into crying, her small body arching and kicking to free herself from my grip. I stood frozen, stiff as a tree trunk, not reacting. Lệ rushed over, cradling the child against her chest.

“Uncle loves you... oh, oh... uncle loves you,” she cooed.

I turned silent, like a stone, and walked out to the garden. I would remain this way during my stay at home. Silent, drifting, slipping like a whisper into things and embracing them with a tenderness unspoken. I looked outside, waiting for the confusing paths of memories to catch up with me. Memories? No. I had no past; I only had an existence that reverberated like waves endlessly lapping against the shore. Sensations, thoughts—they still trembled, untouched by time. I floated aimlessly in the present, in lazy, indolent days, surrounded by landscapes under a sky unchanged, familiar to my eyes. The decision that loomed, I held tightly within my hollow heart, not yet ready to let them rise to the surface.

The cracked, dry path circled the garden, where coconut tree roots snaked across it. The canal water, tinged yellow. The wobbling monkey bridge over the stream. The grassy trail leading to the fields, and the pale sky, signaling the coming rainy season. The marshland was covered in reeds, where the flocks of whistling ducks had already flown away. In the dry season, they returned by the thousands, roosting in the marsh, and in the evenings, they darkened the fields with their soaring flight, their frantic chirping filling the air. Morning blurred away quickly, dissolving with it the regions of imagination my mind had conjured. Some mornings, I wandered along the village road to the dock, standing still by the shore. The mud, dredged from the river's edge beneath the water coconut palms, was sticky and black. The inlet, leading to the river, still bore the imprint of footsteps in the muddy banks when the tide was low. I watched the placid surface of the water. The town, distant and cold, was hidden away.

Suddenly, I wondered: what if I had never crossed over there? What if I had only grown up in this remote village? I would have lived a very different life. I wouldn’t be Trí—I would be Uncle Three, the son, the boy, the man of the house... Trí. Trí. So many people called me by a name that nobody here knew. I was no longer my parents' child; I had been born from other people. (People from somewhere else, somewhere unknown to me).

I remember Diệp, remember the final moments of our adventure. I had pulled her into a frenzy of awakening. How foolish she was. Diệp, wasn’t it? You were my lover, the face of death. Why was I saved? Why was I torn from Diệp’s grasp? The darkened morning never faded into the past. Diệp’s pale, sickly face, after the night of torrential rain, panic-stricken in our sudden flight from the town still asleep. The mist-covered town, the sound of hooves on wet streets, the rumbling of trucks, sputtering in the cold that hadn’t yet lifted. The bus, empty but for the two of us, Diệp’s head resting on my thigh in the backseat. Mist covered the fields, the gardens, the rivers greeting us halfway down the slopes. We were rushing toward our promised destination, that place of perfect silence—the realms of madness and death.

Those late, exhausted slumbers, steeped in the air of old times, like the dim, dying sunlight on the fields, crushed all feelings into unconscious terror. When awoke, I still held on to the indelible images, the imprints of existence’s rhythm. Encounters that unveiled the self, unveiled freedom. Faces that leaned in, searching for shadows. Events that had pushed me to choose my fate. Hour after hour, I withdrew into silence. That silence moved me closer to things, to life itself. The chaotic whirl around me was no longer audible. Everything had become still, calm. I had stood behind death and could do nothing. To live was to be drawn into forces beyond oneself, in the rhythm of relentless recollection and resistance.

Perhaps Lệ had a new lover now, every evening she would carry the baby down to Đình village. In the past, I would have glared at her with scornful severity, and she would sneak around like a criminal before a judge. One afternoon, thinking I was asleep, my mother advised her to be cautious, not to provoke my anger, reminding her of my past disdain and contempt every time she tried to defend Lệ. Back then, I had said, “Don’t ever bring that up to me again… vile women, depraved creatures.” Lệ bowed her head in silent resignation. She was talkative by nature, always laughing. I punished her by never speaking to her throughout her pregnancy and the birth of Liễu. Later, I treated her like a subordinate, only issuing curt commands.

Lệ had studied up to the highest grade in primary school; she was smarter than I was. When we were younger, we attended the same school, and every day she would take me near the classroom door before returning to her girl friends; after class, she’d wait for me at the school gate with packets of gooseberries mixed with shrimp paste or guavas and cashew fruit. On the little ferry that drifted across the river, she’d loosen her hair clip, letting the wind carry her hair, and she’d splash the river water with me, always teasing me when the ferry rocked in the middle of the stream, making me startled. She was four years older than me, two grades ahead. At seventeen, her hair slicked with coconut oil, wearing pristine white clothes, she fell in love with Tạc. She wrote him long love letters on thin blue paper, and every night, she would read them to me at the study table. Tạc had joined the resistance, and the letters he sent her were written on scraps of squared paper torn from a notebook, densely packed with words that she proudly showed me. I remember one line: Loving you, I cannot die; I will return. I never met Tạc, but through Lệ’s letters, I fell in love with him too. Occasionally, Lệ would ask mother’s permission to go down to Chợ-Lớn to meet Tạc when he passed through the town on assignments. We’d wake up early, holding hands as we walked to the ferry dock, the village road still empty beneath the dreamy morning sky. I would stand on the shore, watching her board the boat, reminding her to send my regards to Tạc. I followed her with my eyes as her figure floated away, her white bà ba shirt like a porcelain vase gliding through the trees of the tow. When she returned in the evening, her cheeks flushed, her breath fragrant, she would sing “reform” songs. She recounted the day she spent with Tạc in an affectionate voice, and I listened, spellbound. Once, when rumors spread that Tạc had been shot dead near the Y-shaped bridge, she wept for days, threatening to take her own life. I urged her, “Sister, you must live. Live on and don’t ever marry.” When Tạc regrouped to the North, she went to Cao Lãnh to join him in the resistance zone for a week. I thought she had followed him for good. When she returned home, she was depressed for months. But just a year after Tạc’s death, she became pregnant. Liễu was born with her mother’s surname; I didn’t know who the father was, and I didn’t want to know. I couldn’t understand her betrayal, and I couldn’t forgive her. I banished her from my thoughts, out of my sight. I grew up, alone, wanting to forget everyone dear to me.

Now, I look at Lệ as though she were an acquaintance whose name I couldn’t quite remember. During meals, she feeds her daughter Liễu while talking to my mother, occasionally glancing at me. I kept my head down, occasionally answering my mother’s questions in a half-hearted manner. Sometimes, I spoke to Lệ through Liễu. In the evenings, I wandered aimlessly in the garden, numb to any feelings. I walked through the air of old days, with the lurking threat of a crisis. And I told myself: there’s nothing left. Nothing at all, Trí. Yet, I knew I couldn’t stay silent forever—those around me wouldn’t leave me in peace.

One evening, standing hidden in the shadows by the window, I caught sight of Lệ returning home. She peered in, seeing the bed curtains drawn, thinking I had already fallen asleep. She stood there, outside the window for a long time, like a ghost materialized. The moon no longer rose early; at midnight, I jolted awake, glancing out the window at the brilliant light of the late moon, thinking I could still see her silhouette. I recalled the days when Lệ had stopped going to school. I carried my books alone, walking to class, sometimes following carts loaded with hay with a couple of friends, or wandering into distant villages, chasing after empty horse-drawn carriages, balancing one foot on the iron footrest as we rode out of the town, or sneaking into the back of freight trucks headed to the riverbank for cleaning. I’d lie back as if on a bed of leaves while the clattering ox cart rumbled down the dirt road beneath the shade of bamboo groves on those hot summer afternoons. The driver, half-asleep, paid no mind to the mischievous children, occasionally cracking the whip on the cart’s shaft with a sharp snap. The desolate afternoons on the riverbank, when the children's laughter had died down, the truck sputtering and failing to climb the slope after being washed, left me filled with dread, afraid that night would descend before I could return home. The fields, the trees, the friends, the workers who had made the ride so joyous now became terrifying threats. In those moments, I missed Lệ, missed her teasing laughter in our garden.

I thought Lệ, these past few days still lingering behind me, had something she wanted to say. I was suddenly startled by the strange beauty I had glimpsed in her under the moonlight in the garden the night before—there was a faint resemblance to the mysterious figure of Thuận. Thuận. I sat up, struck a match, and held it to her photograph. I don’t know when I had opened the frame and allowed the flame to consume the image. I jerked my hand away when the fire licked at my finger, dropping the photograph to the ground. The flame flickered, lonely and fading, like a life extinguished. I stared out at the night, the world teeming with creation outside, listening to my mother’s quiet sleep and the restless turning of Lệ. Liễu, deep in sleep, whimpered and cried out, her mother’s soft lullaby rising to soothe her. A little while later, my own tired tears moistened the corners of my eyes.

That very moment, the block of ice encasing my solitude suddenly melted; the night penetrated my body, stretching an intense reality through everything around me. I struggled to rise above the depths of my mind, submerged in the surreal realm of dreams filled with truths. And somehow, I found myself crying, small, short sobs escaping me. In the silence, I heard the distant chaos beyond my consciousness, and the familiar habits returning. I whispered, Trí, you’re not crazy. You’re still alive…

I stood on the porch, the door behind me still slightly ajar. In the garden, moonlight shone as bright as day. Beneath the dense canopies of trees, the wind drifted through in a distant, shapeless murmur. By now, mother and Lệ would be deep asleep. They had taken turns holding little Liễu all night. The child had come down with a burning fever, crying incessantly, finally quieting just a few minutes ago. Her piercing cries cut right through to the nerves, making everything feel fevered and restless; at times, her wailing stopped so abruptly, mid-scream, that it seemed she’d forgotten how to breathe, her limbs twisting and clenching. (Once, in the marketplace, I saw a woman step down from a horse-drawn carriage only to collapse in the middle of the street, her limbs convulsing in spasms, twitching like a severed lizard’s tail, foaming at the mouth.) Those convulsive movements, the uncontrolled jerking of limbs or entire body—I've felt them myself, often in that hazy realm just before deep sleep, when consciousness wrestles in a dim whiteness it can’t break free from; after each episode, I would feel as if I had escaped my own self, panicked and heavy-hearted. The gentle lullabies of my mother and Lệ drifted through, carrying a sense of calm that seeped over body and mind like a slow-moving breeze. And when both the crying and the lullabies finally faded into the faint glimmer at the far edge of the window frame, I would stealthily climb out of bed, careful not to make a sound, change my clothes, and slip out the door. Just as in that pale morning with Diệp, I carried nothing. No luggage, my hands free, my mind light with the hazy weightlessness that feels ever vulnerable to intrusion of needless thoughts. Trí. The name echoed faintly in my mind, a voice—was it my own, conjured in need, or someone else’s calling to me? Trí. Trí. Trí… those sounds reaching back to earliest memory, a child hearing but understanding nothing, yet listening intently. Then the world outside gradually crept in, binding him, until only unconscious movements remained purely his own.

— Trí.

This time, the call echoed grandly in my head and out in the open air, resonating from the deep dark, along with the sound of the door creaking behind me. A figure stood framed in the doorway, face as pale as paper, eyes dark and shining. It’s Lệ.

— You’re up early?

— I’m going for a walk.

I stepped down to the garden path, the scent of night flowers thick in the air. Barefooted, Sister Lệ whispered as she walked, heading straight toward the gate.

— I’ll come with you. Liễu’s fever has eased, she’s asleep. I couldn’t stay in bed, just needed a breath of fresh air.

I pushed open the creaky wooden gate, nearly hanging off its hinges, and we wound deeper into the village. Alone, I would have taken the path down to the river, crossed over to the town. The houses and streets awaited the dawn—a dawn of Thuận, of Diệp, a dawn like the mouth of a grave swallowing up the restlessness of the night. The town lay there like a frontier outpost of some distant country. Dogs barked from either side of the path; one or two slipped through the fence and trotted behind us. Lệ called each by name, softly pushing them away. The dense shadows blocked the path, with pools of moonlight spilled here and there on the ground, trees and plants breathing softly all around us. Lệ gradually caught up, stepping close to the hedges in the narrow lane, her sleeves brushing against the leaves with a faint rustle. The garden trees grew sparse, the sky lightened over the grassy fields, the path, the bridge arching over a small stream, and the open fields beyond. I stopped at the top of a small incline; the road continued over the bridge, disappearing into the thicket of tightly packed nipa palms, leading to the swamp beyond, while the area where we stood was wide open. Lệ sat down on the bridge planks, letting her legs dangle and sway, her uncovered hair casting an odd look. Far out across the fields, no rooftops remained visible amid the sparse trees, just a high, bare strip of land sloping like a fortress wall, lying exposed and ashen under the moonlight.

— What’s over there?

— Where? Ah, they’re setting up Strategic Hamlets in that area. Ours will be next soon enough.

Water trickled under the bridge, dogs barked in the village, and crickets chirped sporadically in the grass around the small rise. The distant bugle sounded in intervals, echoing from the guard posts around the half-built hamlet. Lệ sighed, her breath clearly audible: more fighting, endless fighting. Didn’t I tell Hiệp once? Someday, where we are, the war will spread like wild over the desolate undergrowth. What else can we do? Really, what can we do? We wandered on the edges of swampy reeds, skirting the patches of illusion outside the thorn-fenced walls.

— What are you planning to do, Trí?

— In a few days, I’m heading down to Saigon.

— To work, or to go back to school?

— Go back to school?

I let out a dry laugh at Lệ’s suggestion. The idea of returning to school was absurd. She glanced over at me, raking her fingers through her short, shaggy hair, her back slightly hunched, face turned down towards the flowing water. A night bird cried from the fields, its shadow invisible in the darkness. The world suddenly stirred in desolate quiet.

— I’m sorry.

Lệ fidgeted, unrolling the cuffs of her sleeves that were pushed above her elbows. I looked back toward the village, hearing faint sounds of the approaching morning and the wind gusting in waves. She sat there, hugging her knees like a lost child on the bridge. My face felt cold and damp. The moonlight was fading, casting a hazy gleam. Lệ seemed about to say something more, but I turned away.

— Let’s go back. Better check on Liễu in case she wakes up.

I waited for her to pass in front of me, and as she walked by, she stirred the air with a faint warmth like the breath of swaying grasses. Suddenly, I wanted to reach for her, to grasp her by her broad shoulders as I would have with Thuận, certain she would tremble and recoil, breath caught in fear, stammering, unable to form words. I’d shake her violently, like one shakes a fragile tree, ruthless and relentless, shaking until she finally broke down in tears and my anger was sated.

Tạc didn’t die. He returned, she said. How could one expect… on the very day she left for the regrouping area, he came looking for her in Chợ Lớn. It had been misinformation—he was alive and well. A few days ago, she’d met him down in Đình village. Today he would gone to Bến Cát and would be back in a few days. She asked if I wanted to see him. See Tạc? What did that even mean to me now? Tạc. Who was he? Our childhood hero, Lệ’s lover—the days of youth, were they still there? But we weren’t. I had grown up; I had met Hiệp, met Thuận, met Diệp, and Lệ now held little Liễu in her arms. Is it true, that first love is unforgettable? Liễu lay in her mother’s arms, her face flushed and swollen, eyes heavy with sleep, suffering from a rash. Her grandmother had gone to the market for medicine; only the two of us remained in the house. All the doors and windows were closed to keep out the midday sun and wind, shadows ebbing and flowing around our faces as the light softened then brightened again.

— Seeing him again felt like a ghost rising from the past. Strange… I was so frightened.

A short laugh, meaning elusive. Lệ’s tone still carried that same innocence, pure as the day she used to write letters to Tạc. Has nothing really changed? She sat at the foot of the bed, her body slightly swaying, causing the mattress to shift. I stood up, turning to the closed window, asked:

— And what about Liễu?

The question rebounded forcefully, echoing like a ball thrown against a wall, quicker each time. And what about Liễu? What about her? How to think about it now? She lay there, plain as day in her mother’s arms. After a long silence, Lệ spoke softly:

— He thought I’d gotten married. And that my husband had died.

I leaned my waist against the edge of the table, staring at the stack of books, the bare picture frame. What was there to question? The truth, so easily believable, lay bare before us every day. But what difference did it make? I should have felt furious.

— Do you believe that?

Liễu gave a faint cry, and Lệ adjusted her hold, making the iron springs of the bed frame groan. Maybe Lệ did believe it, too. Why not? She was alive, and memory was an obstacle. Living like a flowing stream, like a still cloud—isn’t that how it’s meant to be? To erase everything in the terror of nature and the fury of history? To live above, beyond, and master all the truths deemed necessary. When I turned to look at her, Lệ had shifted Liễu in her arms, gazing softly into her daughter’s face.

— Trí, why are you so cruel to me?

That question—Diệp’s question. Was I truly cruel? I only wanted to ask, to ask Diệp, to ask Thuận, to ask Hiệp, to ask Lệ just as I asked myself. Because I understood nothing, understood no one, and didn’t want anyone asking me such questions. Was I truly cruel? I scoffed. Each question already held its own answer—why deny it? Hadn’t Hiệp himself accused me of always stirring up trouble?

— I’ll ask you one last thing. After this, I’ll never ask you about anything again. Whatever’s in the past, let it stay there. Who is Liễu’s father?

— I wanted to tell you about this, too.

— Then tell me.

Lệ adjusted her position, hesitated for a long moment.

— Even I… I don’t really know him.

A lie. She still feared me, like I was some stern judge, and didn’t dare tell the truth. I didn’t believe her, not for a second. I dragged a chair to sit directly across from her. Tears glistened faintly in the corners of her eyes, her bewilderment and fear plainly visible. She clutched Liễu tightly to her chest as if to shield herself; the child lay in a pitiable half-sleep.

— He was a northerner who had come down south, yes, all the way back then. I left for the regrouping zone for a few days and didn’t see Tạc, then returned to Saigon. I thought he was truly gone. I felt lost, I didn’t want to come home, so I wandered in Saigon and met Liễu’s father.

— A coincidence?

— He’d just arrived from the north a day or two before, wandering around looking for someone he knew. He asked for directions, but I barely knew my way around Saigon.

Those were the days I first began to have my own plans, leaving her alone with her love. She stepped off the bus at the station as the late afternoon sun slanted down, the bus having picked her up somewhere along the road cutting through fields glinting with water under the sun; a young woman standing on the grass verge, one hand holding a conical hat, the other clutching a bundle of clothes. The bus had turned back to the dirt road, disappearing into the fields. In a Saigon being transformed, disfigured, she shuffled along like someone from the six provinces looking for work, like the displaced driven from their hometown. She too had just been exiled from her own homeland; the love she had thought would be her eternal refuge now left nothing but pain and panic. Loving you, I cannot die. But by then Tạc was already gone. Along those deserted streets stretching through the city, she walked alone, destination unknown, men pausing along the roadside to follow her from the shadows of dim sidewalks, murmuring brief, idle flirtations that soon drifted away behind her. Late that night, Lệ stayed at Uncle Six’s house in the Bàn Cờ alley. She didn’t want to go home the next morning. The man she met held a street map of the city, blurry with smudged colors, studying it intently, while the edge of the road bustled with cars pressing in to make their way through. He asked her something, and Lệ answered. They took the bus to the outskirts, then circled back on near-empty buses filled only with sunlight and wind. One spoke of the North, the other of the South. Lệ wanted to know about Hanoi, to hear about Hanoi, that city where Tạc might have gone, bringing her along; it had already become her imagined homeland, where their love might have flown ahead, waiting to greet them in hopelessness. By noon, Lệ got on the bus back to the province, arranging to meet the man in front of the train station the following week. During the time I was detained, she used the excuse of inquiring about any news to go to that meeting. She wandered the streets with the man, resting on park benches with no promises made, no plans laid out, before returning to his riverside house, at the foot of an iron bridge. The bridge hummed with traffic all day, while the house, propped on stilts, hovered over the water, wooden planks trembling beneath footsteps from neighboring homes. She would spend whole afternoons, even full days there, and I was entirely unaware.

— I loved him the same way I loved Tạc. Is that possible, Trí?

She became pregnant with Liễu during Saigon's chaotic days. The man had disappeared without a trace. For weeks, she would come to gaze at the locked room, with nothing inside but a thin mattress on the floor and two small stools. That man had nothing but those. She managed to get the door open, lay down, and rested there, waiting with the exhaustion of a expectant woman. At times, she thought of ending it right there but clung to a flicker of hope to see him once more. She paused to breathe, holding Liễu tightly against her chest as if to quell the surging emotion. The baby wailed fitfully in a fevered sleep, and Lệ rose, pacing back and forth, rocking her child. Her silhouette blurred in the dim light as she carried Liễu into the inner room. I opened the window. Outside, the garden shimmered in the light breeze, and the noon air grew quiet and light. Sunlight spilled across the dented mattress Lệ had just left. She came back, no longer holding Liễu, her face flushed as if from sunstroke. She sat down in the same spot, her head bowed, much like when she sat on the bridge that morning.

— I persuaded Diệp... Poor Diệp, she listened to me, she pitied me. I never thought I’d be the one who caused her death. Trí, did you know? All I wanted was for you both to be happy, so I told Diệp to ask you to run away together. Only I understood you because we grew up together, didn’t we, Trí?

Isn’t that right, Trí? Isn’t it, Trí? At the end of the row of trees, two dogs chased each other, rolling in the dirt. In the village path, footsteps scraped the hard ground, and the rhythmic drumming from the marketplace drifted up from the riverbank. Lệ tilted her face to the slanting sunlight that glared across her upturned face.

— I’m sorry, Trí.

I didn’t want to speak, didn’t want to hear anything more. I looked into the space before me, quiet, sad, and brightening in the light. After a while, I told Lệ:

— Don’t tell Mom. Tomorrow I’m leaving. I won’t be coming back, so you’ll have to take care of her on your own.

Beneath her smooth, taut blouse, Lệ’s chest still heaved with shallow breaths. She turned her face toward my father’s altar, where a dim oil lamp flickered from inside its red-painted cover. Outside the garden gate, there was the soft clatter of movement, then footsteps on the brick path.

— Alright, mother’s coming in; go on inside.

I lay down on the bed, listening to the sounds of water boiling for washing, mingling with soft sniffles, as my mother questioned Lệ about Liễu and me, my mind weary and flushed with the day’s heat.

I had no idea what time it was when I woke, caught in a stifling silence, as if everyone in the house were dead, or perhaps I was the one awake in the realm of the dead. Tonight, little Liễu didn’t cry, but lay in a feverish daze, lulled by the lonely murmur of my mother and Lệ, more unsettling to me than ever. Here, sweetheart, poor little thing; does it hurt, are you too hot? Don’t you care for your mother? Tell me where it hurts, darling, sweet darling of mine.

— You’re talking nonsense again. My mother scolded sharply.

Did you hear that? Your grandmother’s scolding your mother. Nobody cares about your mother, no one at all. Liễu only made faint murmurs now and then.

“Hush, oh hush…

If you, my dear, wish it to end,

Your harsh words tear our bond apart.”(*)

When she was young, Lệ had never learned lullabies, and during the time she loved Tạc, she only sang reform songs. Now she had become a genuine woman, her voice softened, resigned, patient, slipping through like the gentle, shadowed waters of the river winding through gardens. Hush, oh hush… Her lips barely parted, drawing out each note in a whispered sigh, like a breath close to the ear. It was a summer afternoon trapped in a heavy night: I had just emerged from a dream.

In the dream, I saw a stranger walking beside Lệ in a time far removed. His tall, ungainly figure drifted through the crowd on the sidewalk. I recognized him—Hiệp. “My name is Lệ.” But Hiệp didn’t hear; he gazed off ahead, holding Lệ’s soft, feverish hand. They both vanished into the crowd. I asked, “Don’t you know who she is…?” “I don’t know. I wasn’t paying attention.” I threw myself at him, striking his face, his head, his neck with all I had. Hiệp staggered like a drunk, eyes dazed. “It’s not me…” “It’s not me,” he mumbled, until I was exhausted and slumped against the wall. Hiệp looked at me with hollow eyes, and an endless sadness settled between us. He said something, and I shouted, “I’m Trí, don’t you remember?” He shook his head and murmured something again. I kept shouting, “I’m Trí, I’m Trí, I’m not mad!” Hiệp laughed—a solitary laugh echoing against the walls. I collapsed to the pavement, howling like a dog whipped by that grotesque laughter. Then I wept with wracking sobs, like that evening I had run to the riverbank and buried my head. When I awoke, I realized I hadn’t been crying at all, though the echoes of the dream still lingered on my face…

Suddenly, I heard machine-gun fire crackling in the fields, far off toward the Strategic Hamlet. Dogs barked in waves, carrying through the village. Then silence again. Sporadic gunfire started up, stirring the distant dogs. In the stillness, drumbeats reverberated, punctuating the gunfire like mocking laughter, blending with the endless uproar of the dogs. The clamor seemed hemmed in by the walls around me, leaving an eerie silence beyond. When the shooting ceased, it opened up a vast, bottomless sky, from which a loudspeaker suddenly blared—its words distant, indiscernible. Were they calling out to one another? The sound, faint and faraway, didn’t fully reach across the empty fields, as drumbeats chased and drowned it out. The pulsing drumbeats pounded through my ears, through my chest, like the racing of a restless heart. Outside the window, the sky glinted against the leaves. A rumbling explosion jolted the trees in the garden. The dogs had fallen silent; only the frantic drumbeats remained, and the relentless rumble of artillery growing ever stronger, shaking the ground.

I went out to sit on the ceramic stool on the front porch. The gunfire had completely ceased. Silence pressed around and within me, wrapped in a faint, ghostly light that felt beyond time. For a long while, I heard the faint murmur of water flowing restlessly in the stream beyond, the rustling of leaves, movements like dancing illusions. My eyelids bore heavy and dry traces of tears, casting blurred, unchanging shadows onto my vision. Nothing left to torment, no further torture; this path you’ve taken—you must follow it through. The place you had agreed to meet your comrades—you were late but you will eventually reach it. Only Hiệp remains, somewhere out there, a mix of resentment and redundant attachment.

The night, its dim light sinking and stretching with the chill and the wind, lingered on, uncertain of when it would dissolve into dawn. It felt as though I had lived these exact moments once before, though I could no longer recall them clearly. Bit by bit, I forgot myself, merging into a whiteness like the patch of sky threaded between the trees in the garden, out on the field. A shiver hit as I realized I had exhaustively spent my entire life up to now; every moment hereafter would be but a mere repeat, a mediocre mimicry of the past. Fear sprouted thorn-like from every inch of my body, unyielding, relentless.

With an imagination lashed and pushed by sudden pain, I saw everything that had unfolded between us in piercing lucidity. I looked into myself as if gazing into a dream—a never-ending dream, so long as I remained awake. Passion wasn’t a hope; I had grown up consumed by a fierce passion hidden beneath a mask of stern indifference. That’s what Hiệp had said. But what about Thuận? And Diệp? And even Hiệp himself. He was still alive, yet to me he was as distant as a shadow. What force had propelled these lives to merge with mine into what felt like Fate? It was nothing more than the solitary passions that drove us to despair. Truth suddenly surged up from nowhere. Blank spaces filled in. The drama echoed in ferocious waves. I came to understand everything that had taken place before, behind my back.

The night flowed on with the dim moon like an unstoppable bleed. At dawn’s first pale light, I would slip away like a thief who dares not face anyone. I, too, would vanish.

Anh Hoa dịch

(*) Translation of a Southern Vietnamese lullaby: “Ví dầu tình bậu muốn thôi / Bậu gieo tiếng dữ cho rời bậu ra.” In this context, “bậu” is a term of endearment commonly used in Vietnamese folk songs, meaning “my dear” or “my love,” though here it conveys the sense of a lover who has grown distant or cold.

một Cát lầy khác

la vie est ailleurs

Dương Nghiễm Mậu: The Age of Poisonous Water

pourvu que je soit un autre